Leaving the U.S. to reclaim a legacy

Why moving abroad feels like my proudest achievement as the child of immigrants

I never needed a bedtime story read to me as a child.

Mine were murmured around me as I drifted to sleep in the laps of my elders. There were no pages, just my Guyanese grandmother, with her gold-capped teeth glinting as she smiled just above me, or my parents, their warm bellies vibrating with laughter as they recalled a time and a place I was too young and too far away to know.

“Eh eh! Lawd have mercy. I gon talk becah I know is what!”

I always preferred the sucking of teeth and the clapping of hands to the flipping of pages. This recounting? These precious memories, delivered in warm, familiar patwa? These were stories that were so real they didn’t require imagination. They were about how my mother slowly traded her tree-climbing tendencies to cook and care for five brothers. How my grandmother traversed icy New York sidewalks to clean hotel rooms at New York’s Waldorf Astoria — while grieving her husband, parents, and son. How my parents ‘learned to be Black’ from baffled peers, flattening their accents and donning new attire only to go home to bake and saltfish, porridge and cloves, and tales of how hard they must work to get from there to here.

The foundation of my family story has always felt like this: they are from there, and I am from here. It always felt like a story that happened before and apart from me.

The distance never made sense. I am from them, I belong to them, but I worried that our cultural ties stopped at the shape of our eyes. I’ve always wanted a story we could share.

I should have told my parents I wanted to be an immigrant when I grew up, just like them.

Instead, I told them I wanted to be a journalist. (Which, if we’re honest, is a vocation fed by curiosity, conviction, and grit — all qualities immigrants have used to survive.)

I should have told them that I didn’t just want to make my degree my primary goal; to just pay off 128k in student loans; to just be a law-abiding citizen, buy a home, or find faith.

I checked those accomplishments off my list because baby Ashley learned a script from her immigrant parents about how to be a good American. And none of those goals, though lovely, feel like ones that connect me to them.

Essentially, being a first-generation daughter of Guyanese immigrants means being the first in my family to do lots of things. And being the first means having lots of experiences that are uniquely and isolatingly mine. When you are the first, you are on your own path, and the more distinct that path looks to the people who made you, the better. My immigrant parents have striven, sacrificed, and prayed that my life would look markedly different than their own. An observable contrast between our early-life experiences was their deepest desire.

The more I think about it, there’s a chasm between immigrants and their children born into a chosen land. Yes, immigrants bring their pasts into their parenting: there are traditions, food, music, and values they pass on. But there is much they choose to move away from.

I get that, I do. But perhaps parts of my family history were meant to be repeated.

It wasn’t always this way. My Caribbean parents told tales of hungry bellies, single mothers stressed beyond belief, not enough resources, time, money, or joy. They are both from families of eight, with fathers who died far too early, and family trauma still buried in their South American lineage. Most of what baby Ashley heard about my parents’ first home was ‘not enough.’ Not nearly enough.

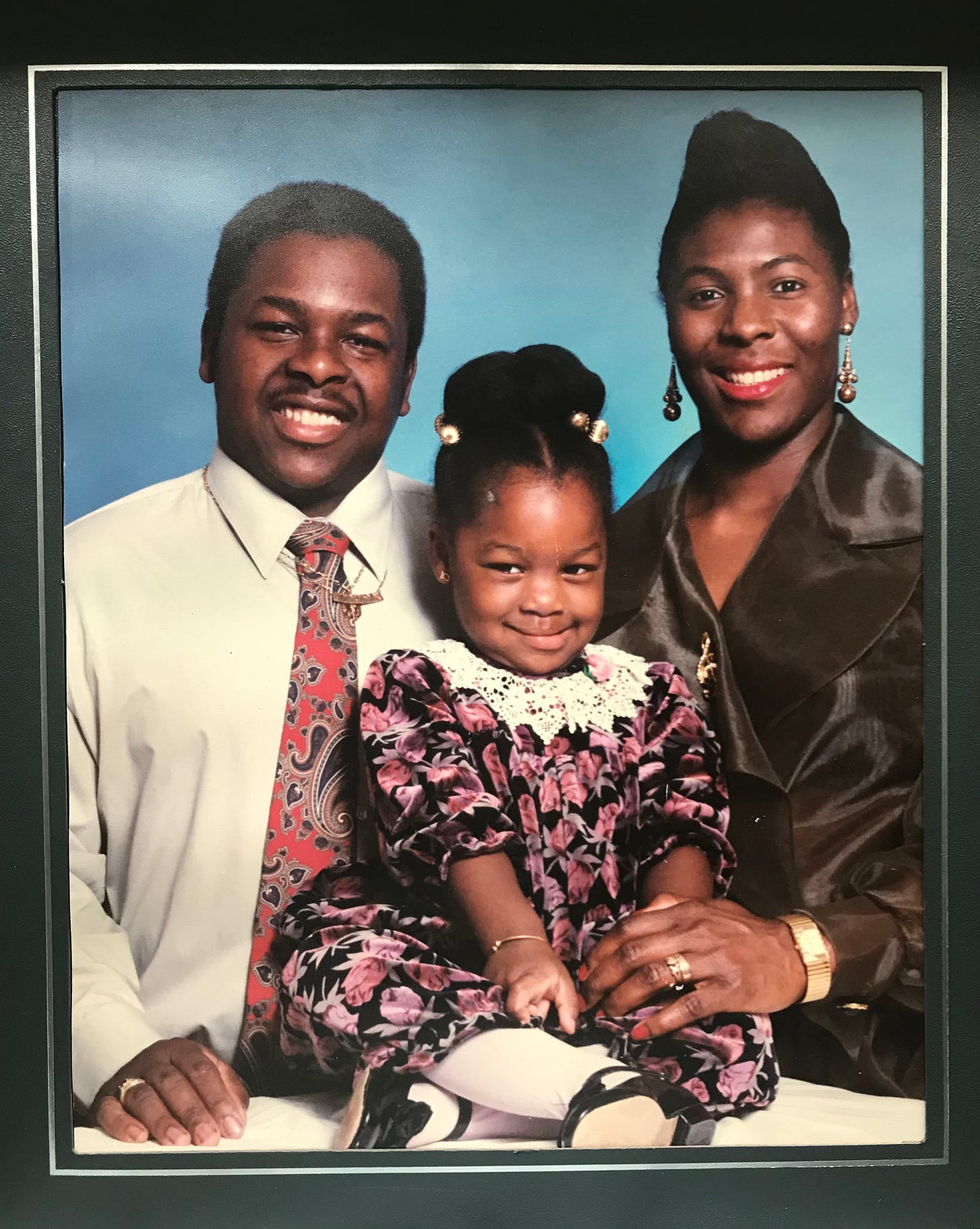

So they gave my brother and me more than they dared dream: they were the glue of their community in northern New Jersey, they’re still madly in love 35 years in, and they worked so my brother and I wanted for nothing and had access to everything.

So why leave all that? What more could I want?

. . .

About a year ago, as I was preparing to make a home abroad, I started practicing breathwork with a crunchy, granola white man in rural Durham, NC. I did a lot of breathing and a lot of crying in our time together. I hadn’t realized just how forcefully and painfully I’d been holding my breath in the States.

I remember one session in particular — I sat on the ground, half-hyperventilating and half sniffling, my eyes swimming with tears. I muttered, exasperated, to both him and myself, “I feel like I’ve worked too hard to feel like this.”

He asked, “What is the story you have been given about working hard? What has working hard been taking care of for you?”

Just like that, my life’s story played out in my mind’s eye — the $2,795 monthly payments to SoFi (each hard-won thousand a testament to a college degree my parents desperately wanted for me). The jobs I stayed in too long. The bosses whose eviserating feedback I didn’t believe I had the right to refute. The social opportunities forfeited, the risks never taken. The straight and narrow road was a sacrifice I bore to ensure a blemish-free future.

The room fell silent. “I think I work hard to feel close to my parents,” I said. “I think I don’t recognize myself or my place in the story of my culture without the presence of sacrifice. I’m afraid that if I don’t work hard, I won’t belong to them.”

I was desperate to be connected to my family story, by any means necessary. And it felt like their immigrant story was rooted in strife, so to belong to them, I had to participate in the struggle.

But after that session, I made up my mind: I’m going to find another way to relate to my parents and my people. What if I walked their path, but in a different way?

Perhaps my parents’ greatest gift to me is choicefulness.

They helped me build the scaffolding of safety in my life so I can make decisions out of security, not fear. So when I say I want to take root in another country, I actually AM living out their wildest dreams.

I am a child who can choose to enjoy parts of life her parents had to bear.

I am a child who can build a life unburdened by the worries they shouldered.

I am a child who can plant too, not just enjoy her parents’ harvest.

I am a child who now has the privilege to reclaim her heritage, on her terms.

A few weeks after arriving in Lisbon, I Facetimed my parents, waxing poetic about hanging my laundry on the clothesline outside our bedroom window. “Isn’t that cool?!” I chirped, watching their eyes crinkle as they smiled. “There’s no way I’d go back to that Guyanese business,” my dad said. “You can have that. I’ll take my dryer.”

A thread of our shared story, decades and thousands of miles apart.

I’ve never felt closer to them.

Here are some other ways you can support our work:

I love this, Ashley! Such a poignant and beautifully-written story. I love the insight woven throughout and how you made sense of their journey, your wanting to belong in your family's story, and the journey you've chosen for yourself. Really enjoyed learning about you here and your writing is stellar!

Thanks so much for this essay, Ashley! I can totally relate to your feelings and experiences as the child of immigrant parents. In fact, your blog reminds me of a panel I saw on YouTube a while back about Black women with Caribbean parents who moved to the US and UK for better lives, only to become expats themselves. It’s a fascinating perspective, and one that I expect to only grow as time goes on.